БИОИНФОРМАТИЧЕСКИЙ АНАЛИЗ ГЕНОМНЫХ ОСТРОВОВ В ЦЕЛЫХ ГЕНОМАХ ШТАММОВ PISCIRICKETTSIA SALMONIS

БИОИНФОРМАТИЧЕСКИЙ АНАЛИЗ ГЕНОМНЫХ ОСТРОВОВ В ЦЕЛЫХ ГЕНОМАХ ШТАММОВ PISCIRICKETTSIA SALMONIS

Аннотация

Патология, вызываемая Piscirickettsia salmonis, является причиной больших потерь в популяции лососевых в Чили. Со временем бактерия выработала устойчивость к терапии, включая антибиотики и вакцины, благодаря разнообразию стратегий избегания, включая образование биопленки. У бактерии есть геномные острова, кластеры релевантных генов, которые изменяются в разных геномах. Целью этой работы был анализ взаимосвязи между количеством патогенных островов и их генами вирулентности в полных геномах различных штаммов геногрупп EM и LF, помимо поиска геномных островов с невирулентными факторами, например, метаболические острова и приспособленность. Кроме того, мы оценили сохранность и вариабельность между штаммами из разных геногрупп, рассматривая LF-89 (ATCC) и Psal-001 в качестве референтных штаммов, анализ геномов используя средние значения используя два биоинформатических инструментов. Было количественно определено около 13 патогенных остров/штаммов, от 1 до 47 локусов/остров с уникальным поведением для геногруппы. Сравнение островов в отношении геномов, более высокий уровень сохранения наблюдается в геногруппе EM, против колеблющихся значений среди штаммов геногруппы LF. Также были обнаружены невирулентные факторы. В целом группа генов EM продемонстрировала большую конвергенцию в сохранении островов между штаммами в отношении патогенной деятельности по сравнению со штаммами LF. Окончательно было обнаружено, что различные транспозиции поддерживают высокую геномную пластичность, а отсутствие подтвержденных генов затрудняло их правильную идентификацию.

1. Introduction

The control of piscirickettsiosis in Chile has been addressed using antibiotics, which has decreased the susceptibility of the pathogen to these treatments

. Piscirickettsia salmonis, its etiological agent, is one of the main threats to the salmon industry, causing almost 60% of all deaths from infectious diseases of Chilean salmonid population . The pathogen was originally identified in coho salmon and corresponds to a Gram-negative, facultative, intracellular, aerobic and non-motile coccoid, with a diameter ranging between 0.5-1.5 micrometers .P. salmonis generates outbreaks of piscirickettsiosis in host fish population, producing systemic injuries with a variety of clinical signs. It is also characterized by functional mechanisms that increase its survival like biofilms formation on different parts of the host and form viable structures on inorganic materials, highlighting its role as a facultative pathogen

.Bioinformatic tools and approaches can provide deeper insights into the genomic foundations of microorganism’s pathological activities. Genomic islands, ranging in size from 10 to 200 kb, play a key role in this context as they contain genes with functional interest that are grouped by mobile genetic elements

. They possess distinct characteristics such as direct repeat sequences, low GC content, virulence or resistance factors and transposons which identify them as islands .Genomic islands have been categorized into 'fitness', 'ecological' and 'pathogenicity islands'

. They can be further classified as 'saprophytic', 'symbiosis' or a pathogenicity island, in the case of bacteria interacting with hosts . These are common among Yersinia spp., fecal E. coli, and Klebsiella sp, with their classification as pathogenic, saprophytic, and ecological respectively being well-established. The presence of the island in Yersinia sp is directly associated with an increase in its pathogenicity. Nonpathogenic strains lacking these islands may restructure their genomes into fitness or ecological islands for optimal adaptation.A previous report analyzed a pathogenicity island with 38.57% GC content, where 23 genes were reported, registering both hypothetical proteins and genes associated with virulence, using PIPS (Pathogenicity Island Prediction Software). The virulence mechanisms of this pathogen and many others can be understood by analyzing pathogenicity islands, mobile genetic elements that rotate between chromosomes and plasmids, possessing genes involved in virulent processes and/or antibiotic resistance. Three genes associated with virulence were evaluated: transcription-repair coupling protein (tcf), Mg-dependent DNase (dnase) gene and lytic transglycosylase (liso). They found a similarity between the above genes and those found in Neptunomonas antarctica, Endozoicomonas sp. and Legionella spiritensis, respectively, and hypothetical proteins that have the potential of being compared against a database for future identification and classification

.The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) has a database containing annotated complete genomes of various strains of P. salmonis, making it possible to compare complete, assembled, and annotated strains and genomes. This includes the complete genome of the original strain isolated in Chile in 1989 (ATCC VR-1361)

. Over 80 complete genomes are available at the NCBI database today, in addition to new approaches from in silico studies, besides bioinformatics tools.This work focused on analyzing the genomic islands in P. salmonis, evaluating the relationship between the number of pathogenicity islands and their virulence genes in complete genomes of different strains of the EM and LF genogroups, as well as determining the presence of fitness islands.

2. Research methods and principles

2.1. Bioinformatics tools and P. salmonis strains

P. salmonis strains Psal-006b, Psal-009 and Psal-011, Psal-001, Psal-005, Psal-069 and Psal-072 were selected because they were isolate from southern Chile after LF-89 isolation date, besides LF-89 as original strain. Genome information was downloaded from NCBI in gbk format (Table 1).

Table 1 - Genomes of strains selected for in silico evaluation of genomic islands

Genogroup | Strain | Isolation year | Species of origin | N° of plasmids | Genome size (Mb) | Annotated genes | Accession number (NCBI) |

LF | LF-89 1 | 1989 | O. kisutch | 4 | 3.50 | 3651 | CP011849.2 |

LF | Psal-006b | 1997 | S. salar | 5 | 3.47 | 3680 | CP038898.1 |

LF | Psal-009 | 2000 | O. kisutch | 4 | 3.56 | 3791 | CP038908.1 |

LF | Psal-011 | 2013 | S. salar | 3 | 3.42 | 3672 | CP038923.1 |

EM | Psal-001 | 1990 | O. kisutch | 4 | 3.41 | 3680 | CP038811.1 |

EM | Psal-005 | 1991 | S. salar | 1 | 3.33 | 3524 | CP038891.1 |

EM | Psal-069 | 2016 | S. salar | 2 | 3.38 | 3626 | CP038972.1 |

EM | Psal-072 | 2017 | S. salar | 5 | 3.71 | 3929 | CP039040.1 |

Two bioinformatics tools were selected for double prediction confirmation of candidate genomic islands. Genomic Island Prediction Software (GIPSy) v.1.1.3 (www.bioinformatics.org/groups/?group_id=1180)

and IslandViewer 4 (https://www.pathogenomics.sfu.ca/islandviewer) were employed. GIPSy allows the prediction and analysis of genomic islands, incorporating metabolic, resistance and symbiotic characteristics, in addition to pathogenic features; it requires two genomes to be contrasted against various databases. GIPSy is an update of the previously developed Pathogenicity Island Prediction Software (PIPS) composed by eight sequential steps with BLASTp analyses against various databases. The different steps in the tool considered sensitivity values and the causality E-value, which were well suited and employed by default. IslandViewer 4 software integrates four types of predictive methods for genomic islands: IslandPick , IslandPath-DIMOB , SIGI-HMM and Islander . It allows to view and download genomic island information for all published prokaryotic genomes.2.2. Locus conservation between genomes and islands

The selected islands were ordered and broken down by each locus present, and the resulting matrices from BLASTp in GIPSy were used as a database for comparison against the gbk file format database.

The identity percentage of each intersected island was averaged to determine the degree of conservation between strains and genogroups. However, strains LF-89 and Psal-006b were determined differently from the rest, so the average included them. The same process was repeated but contrasting the ordered loci with respect to the same islands previously determined. The identity values obtained for each locus were averaged and grouped by island, both to compare with respect to genogroup and island, and to culminate in a comparison between genomes, averaging the values of the islands in each genome.

2.3. Search for non-pathogenic elements in genomic islands

The non-virulent factors determined by BLASTp against databases COG

, ARDB , CARD , and NodMutDB were compared to non-pathogenic genomic islands. The islands that possessed the metabolic, resistance and symbiotic factors were ordered and grouped by their genomic location. They were distributed in a table with column headings arranged as follows: genome (strain), island according to start-end designated by loci, percentage of each factor, and relationship with the previously described pathogenicity island.The islands were broken down by loci, assigning an individual percentage of identity against the database and a percentage of identity with respect to LF-89 as the original strain, to distribute the information regarding the genes encountered in contrast with each strain.

2.4. Description of specific pathogenicity islands

The selection criteria used to analyze islands were most conserved in general, most conserved per genogroup, and less conserved, focusing on total values above 0%. These criteria were used to prioritize the value of the mean difference between genogroups.

Three islands for each category were selected for the subsequent description of their gene identity. GIPSy was used to confirm the islands, and Artemis (https://www.sanger.ac.uk/tool/artemis/), for genome visualization

. Blast2Go (https://www.blast2go.com) was used to analyze annotations and relationships with some processes or functions associated with gene ontology . BLASTp was used to complement the Swiss-Prot database .2.5. Visualization of genomic rearrangement in bacterial chromosomes

The eight bacterial strains under study were analyzed for synteny with the pyGenomeViz library

. The synteny is composed of all strains, separated by genogroups.3. Main results

This study is an update of the previous report , using complete genomes and computer software to analyze genomic islands. The combined use of GIPSy and IslandViewer was used to determine the genomic islands of all eight strains. LF-89 and Psal-006b had different criteria selecting genomic island, because of the scarcity of double confirmation, besides in vitro genomic island for Psal-006b in previous analysis. Psal-009 exhibited the highest number with 16 islands, while Psal-011, Psal-001, Psal-005, Psal-069 and Psal-072 showed 12, 12, 12, 10, 12 islands, respectively (Table 2). Islands with complete intersections detected by GIPSy and reflected in IslandViewer were island 4 in Psal-011 (RS06445-RS06480) and island 4 in Psal-001 (RS06660-RS06695) (Table S1 & S2).

Table 2 - Total number of genomic islands per strain

Strain / Criteria | IslandViewer | GIPSy | Double confirmation | Selected genomic islands |

LF-89 | 28 | 2 | 1 | 13 |

Psal-006b | 26 | 1 | 0 | 13 |

Psal-009 | 30 | 23 | 16 | 16 |

Psal-011 | 27 | 20 | 12 | 12 |

Psal-001 | 28 | 23 | 12 | 12 |

Psal-005 | 29 | 21 | 12 | 12 |

Psal-069 | 27 | 18 | 10 | 10 |

Psal-072 | 27 | 20 | 12 | 12 |

BLASTp was performed against GIPSy for all sequences, yielding a total of 56 databases. The results revealed a total of 100 islands among all strains, with an average of 12 loci per island. The largest islands were found in Psal-011 and Psal-069 with 47 loci. The averaged similarity between strains was established, evidencing that the islands from LF-89 and Psal-006 presented values lower than 75% at the genome level. The strains of the EM genogroup exhibited a higher percentage of identity, indicating that, with respect to all the genomes, they do present higher percent identity values. Another remarkable aspect was the decrease in the identity percentage of the islands with regard to the genome of LF-89, unlike its counterpart, the genome of Psal-072 shown in the eighth column, that was constantly increasing (Table 3).

Table 3 - Conservation of pathogenicity islands with respect to genome in each strain of P. salmonis

Percentage | LF-89 | Psal-006b | Psal-009 | Psal-011 | Psal-001 | Psal-005 | Psal-069 | Psal-072 | LF | EM | Total | Difference |

LF-89 | - | 99.88 | 68.38 | 74.98 | 74.56 | 74.98 | 75.11 | 67.80 | 85.81 | 73.12 | 79.46 | 12.70 |

Psal-006b | 99.07 | - | 69.99 | 69.54 | 72.16 | 69.61 | 69.54 | 68.81 | 84.65 | 70.03 | 77.34 | 14.62 |

Psal-009 | 46.16 | 46.17 | - | 82.39 | 82.37 | 82.37 | 82.39 | 82.30 | 68.68 | 82.36 | 75.52 | 13.68 |

Psal-011 | 52.90 | 52.87 | 98.73 | - | 99.76 | 99.87 | 100.00 | 95.64 | 76.13 | 98.82 | 87.47 | 22.69 |

Psal-001 | 57.88 | 57.80 | 98.95 | 99.51 | - | 99.56 | 99.51 | 96.99 | 78.54 | 99.01 | 88.77 | 20.48 |

Psal-005 | 52.18 | 52.17 | 98.20 | 99.83 | 97.64 | - | 99.83 | 93.38 | 75.59 | 97.71 | 86.65 | 22.12 |

Psal-069 | 53.51 | 53.50 | 98.63 | 99.99 | 99.71 | 99.84 | - | 96.26 | 76.41 | 98.95 | 87.68 | 22.54 |

Psal072 | 46.02 | 46.00 | 99.53 | 94.82 | 94.78 | 94.82 | 94.82 | - | 71.59 | 96.11 | 83.85 | 24.51 |

The two strains with the highest percentage of conserved islands at the level of total genomes correspond to Psal-069 and Psal-005, respectively. Considering genome, the strain with the most conserved islands corresponds to Psal-001, with an average identity of 88.77% between genomes. The most conserved in the LF group was LF-89 with 85.81%, and with respect to EM, it was Psal-001 with 99.01%. The strains with the least general conservation at the chromosome level were LF-89, Psal-006b and Psal-009, but simultaneously showed the lowest variation between genogroups. Psal-011, despite being from the LF genogroup, both values were more alike to those of the EM genogroup, reaching values of 98.82% and 76.13% respectively.

The LF-89 and Psal-006b strains presented the least conserved islands, with values close to 3% for LF-89 and less than 1% for Psal-006b, except for their relationship with Psal-009, with 4.09% conservation between islands. Psal-009 was the one that showed the least difference between genogroups (Table 4).

Table 4 - Conservation of pathogenicity islands with respect to other pathogenicity islands in each strain

Percentage | LF-89 | Psal-006b | Psal-009 | Psal-011 | Psal-001 | Psal-005 | Psal-069 | Psal-072 | LF | EM | Total | Difference |

LF-89 | - | 0.00 | 2.19 | 2.51 | 2.98 | 2.51 | 2.51 | 0.47 | 26.17 | 2.12 | 14.14 | 24.06 |

Psal-006b | 0.00 | - | 4.79 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.46 | 0.54 | 26.31 | 0.48 | 13.39 | 25.84 |

Psal-009 | 1.70 | 1.34 | - | 42.82 | 43.04 | 35.87 | 34.25 | 52.98 | 36.47 | 41.53 | 39.00 | 5.07 |

Psal-011 | 1.92 | 2.36 | 42.52 | - | 77.31 | 70.84 | 69.35 | 41.03 | 36.70 | 64.63 | 50.67 | 27.93 |

Psal-001 | 3.98 | 2.84 | 45.33 | 76.00 | - | 67.08 | 66.75 | 42.80 | 32.04 | 69.16 | 50.60 | 37.12 |

Psal-005 | 1.88 | 2.36 | 44.10 | 70.86 | 69.74 | - | 69.31 | 40.74 | 29.80 | 69.95 | 49.87 | 40.15 |

Psal-069 | 2.25 | 2.83 | 45.47 | 83.65 | 82.09 | 84.99 | - | 43.68 | 33.55 | 77.69 | 55.62 | 44.14 |

Psal-072 | 1.85 | 0.74 | 67.18 | 50.07 | 51.04 | 40.78 | 39.22 | - | 29.96 | 57.76 | 43.86 | 27.80 |

GIPSy analysis revealed that the islands showing pathogenicity features were the most abundant in all genomes, while those classified as metabolic represented 18%. Antibiotic resistance were only 5% of those evaluated, and symbiotic reached 7%, with identical percentages observed in LF- and EM-type genomes (Table 5).

Table 5 - Percentage of factors present in chromosomes of LF and EM genogroup strains

Genome / Percentage | LF | EM | Total | Difference between strains |

Virulence | 33.754 | 34 | 34 | 0.3 |

Antibiotic resistance | 4.75 | 5 | 4.87 | 0.3 |

Metabolic | 17.75 | 18 | 18 | 0.5 |

Symbiotic | 7 | 7 | 7 | 0.0 |

The most conserved islands between strains were LF-89 island-2, Psal-006b island-2 and Psal-001 island-6, with a mean total of 96.63% with a difference of 4.1% between genogroups. From the LF genogroup, LF-89 island-2, Psal-006b island-2 and LF-89 island-8 had higher values of 98.35%, 97.90% and 96.80%, respectively. From the EM genogroup, Psal-009 island-9, Psal-009 island-16 and Psal-011 island-11 had values of 100% for the EM genogroup and a difference between genogroups of 50.00%, 14.90% and 10.00%, respectively. Finally, Psal-009 island-5, Psal-006b island-1, and Psal-006b island-4 stood out.

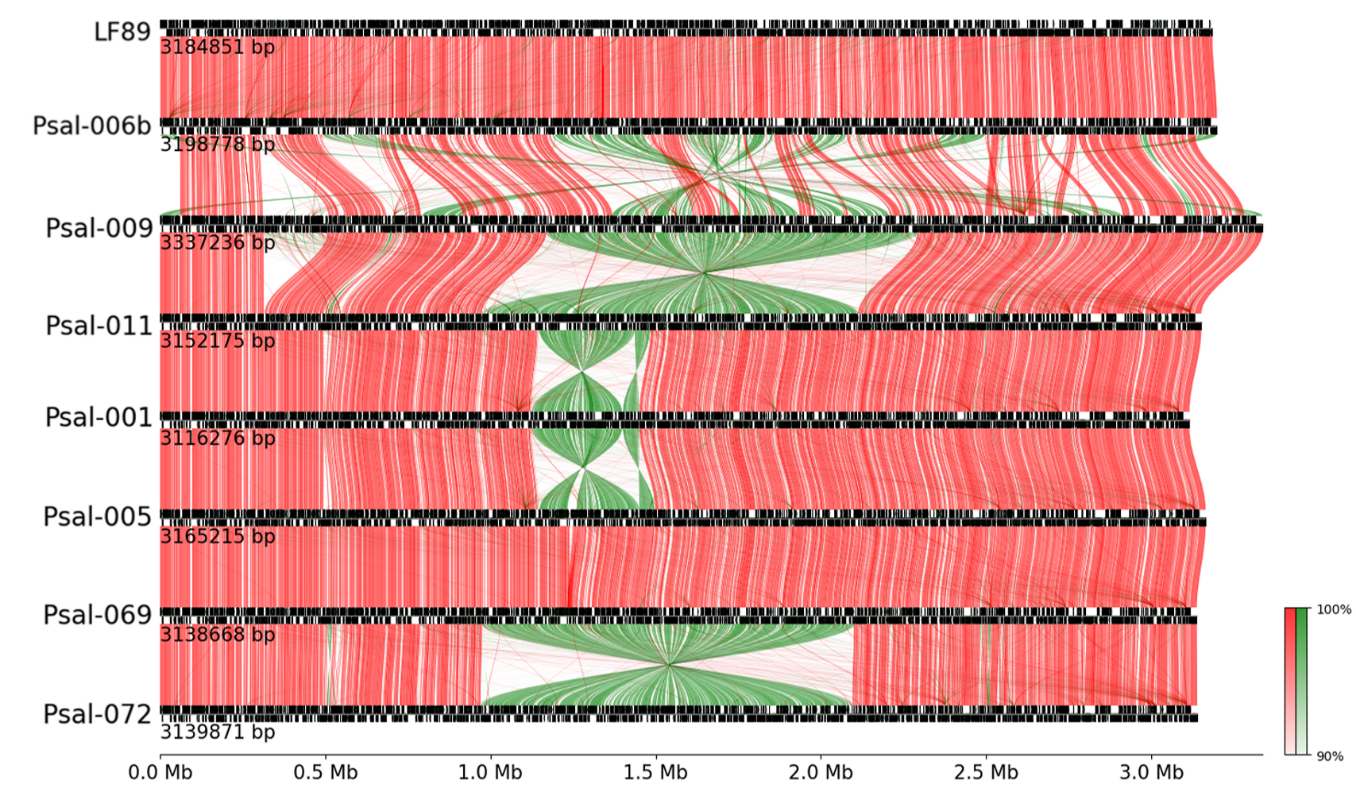

Figure 1 - Complete synteny of bacterial chromosomes of strains of genogroup LF (four above) and genogroup EM (four below), in proportional scale of 3M base pairs with barcolor according to gene orientation comparison, being red for same strand and green in opposite strand

Note: links between genes were filtered, registering only links over 90% identity percentage

The most conserved genes observed in each category were mobile elements, such as transposases and integrases, and genes described in Swiss-Prot, such as fur, bamE, recN, ppnK, and hslO. The second category was the most diverse for presenting bamE, fur, recN, and ppnK, mainly due to the reappearance of islands in both Psal-006b and LF-89. The most conserved islands in the EM genogroup analyzed showed a total of 12 genes, finding genes for mobile elements, transporters, cobalt chelatase, and hypothetical proteins. Finally, 28 genes were found in the least conserved chromosomal islands, with a predominance of hypothetical proteins, genes related to phages, and components of the type IV secretion system (Table S4).

Two islands from Psal-011 and Psal-001, island-4 in each, were composed of two IS91 family transposase genes, a group II intron reverse transcriptase/maturase, and five hypothetical proteins. Of the three hypothetical proteins present in both islands, analyzed by BLASTp at NCBI, it was found that one shared 34.96% similarity, on the part of the two strains, with -lactamase coming from a different strain of P. salmonis, whereas the other two showed similarity to only hypothetical proteins from different strains of the same bacterium. Despite the code difference, both strains shared 86.99% identity with glycine dehydrogenase subunit I and only a reduced relationship with other hypothetical proteins (Table 6).

Table 6 - Description of genes in pathogenic islands Psal-011 island 4 y Psal-001 island 4, compared to LF-89

Locus | Accession of reference | Gene product on Artemis | Loci | Identity % | E-value |

Psal-011 | |||||

RS06445 | WP_032126789.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS36960 F 1349828:1350097 hypothetical protein | 93.10 | 7e-32 |

RS06450 | WP_155049124.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS37535 R 2686852:2688135 IS4 family transposase | 43.59 | 9e-05 |

RS06455 | WP_032126846.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS24390 F 1350302:1350802 hypothetical protein | 86.99 | 2e-82 |

RS06460 | WP_016212251.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS24395 F 1350963:1352066 hypothetical protein | 93.60 | 4e-109 |

RS06465 | WP_054300384.1 | IS91 family transposase | PSLF89_RS31530 F 2759113:2760084 IS91 family transposase | 50.83 | 3e-83 |

RS06470 | WP_075274828.1 | group II intron reverse transcriptase/maturase | No Hits Found 1 | - -.- - | |

RS06475 | WP_052133287.1 | IS91 family transposase | PSLF89_RS25755 R 1615597:1615926 transposase | 53.25 | 5e-19 |

RS06480 | WP_016212039.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS24395 F 1350963:1352066 hypothetical protein | 89.19 | 2e-107 |

Psal-001 | |||||

RS06660 | WP_016212039.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS24395 F 1350963:1352066 hypothetical protein | 89.19 | 2e-107 |

RS06665 | WP_052133287.1 | IS91 family transposase | PSLF89_RS25755 R 1615597:1615926 transposase | 53.25 | 5e-19 |

RS06670 | WP_075274828.1 | group II intron reverse transcriptase/maturase | No Hits Found 1 | - -.- - | 0 |

RS06675 | WP_054300384.1 | IS91 family transposase | PSLF89_RS31530 F 2759113:2760084 IS91 family transposase | 50.83 | 3e-83 |

RS06680 | WP_016212251.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS24395 F 1350963:1352066 hypothetical protein | 93.60 | 4e-109 |

RS06685 | WP_016212250.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS24390 F 1350302:1350802 hypothetical protein | 86.99 | 5e-82 |

RS06690 | WP_032126600.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS37535 R 2686852:2688135 IS4 family transposase | ||

RS06695 | WP_032126789.1 | hypothetical protein | PSLF89_RS36960 F 1349828:1350097 hypothetical protein | 93.10 | 7e-32 |

Note: 1 not found in LF-89. Described as “Group II intrón-encoded protein LtrA” in other P. salmonis strains

4. Discussion

Mechanism of acquisition of genomic islands have been studied, such as the high-pathogenicity island in Enterobacteriaceae linked to integrative and conjugative elements

, and Staphylococcus aureus islands mobilized by helper phages . However, there is not enough documentation on pathogenicity islands in genomes of P. salmonis. To address this, three tools are recommended: Alien Hunter, IslandViewer4 and GIPSy .EM genogroup may have rearranged its islands and genes more efficiently, while the LF genogroup showed fewer independent islands when using the GIPSy tool. This difference in rearrangements can be correlated with the difference in pathogenicity between strains from these genogroups. A comparative study evaluating pathogenesis and virulence in isolates from both genogroups highlighted that the EM-90 strain, equivalent in code to Psal-001, had a higher accumulated mortality and a reduced time to death, compared to LF-89

.The islands analyzed were characterized by exhibiting only mobile elements and low GC content. However, it has been found that P. salmonis induces an inflammatory response together with a positive regulation to produce interleukin-8

and a negative regulation of cell proliferation , at different levels by isolates. Additionally, chemotaxis and flagellar genes, identical to those of Vibrio cholerae and rFLA in Vibrio anguillarum , FlhF and FlhG homologs suggest that P. salmonis synthesizes a flagellar pole . Nonetheless, genes for virulence factors were found adjacent to islands. For example, Psal-001 island 4 was closely related to genes encoding T4SS, systems related to pathogenicity, and to dotA gene, related to invasion and intracellular survival , among others.These have been studied and identified in other microorganisms, such as Staphylococcus aureus, contributing to virulence

, or Salmonella, incorporated through excision and replication by helper phages . This demonstrates the versatility among pathogenicity islands, but this type of information has not yet been recorded in P. salmonis.Databases revealed that 18 non-virulent genes were quantified, highlighting in resistance genes: phosphate regulon sharing 30% identity with the gene encoding BaeR sensor protein in Shigella dysenteriae, and response regulator sharing 43% identity with alkaline phosphatase synthesis in Lysteria monocytogenes. There is evidence of BaeR response regulator in E. coli, related to the drug exporter gene expression in the multidrug resistance system conferred by efflux transporters from the resistance-nodulation-cell division (RND) family

, similar to acrAB expression, related to this family of transporters . For alkaline phosphatase, former studies revealed spatially and temporarily heterogeneous expression in phosphate deprivation in bacterial biofilms . The reference gene in P. salmonis has been described as an unspecified response regulator, stating that this gene could play a metabolic role.Metabolic genes elbB shared 53% identity for uncharacterized protein involved in early stage of isoprenoid biosynthesis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa , important during intracellular survival of pathogenic bacteria

, followed by FAD-binding protein in P. salmonis with 53% identity with pyruvate-oxoglutarate complex related gene of Sinorhizobium melilot allowing us to assume that it is related to tricarboxylic acid cycle in P. salmonis. Metabolic islands can be further addressed by considering the auxotroph presented by P. salmonis, which has allowed the formulation of culture media according to amino acids requirements .The third group of genes identified are symbiosis factors, like the regulon phosphate gene of Rhizobium etli and the phoR gene. Reference genes in P. salmonis were the same for resistance factors category.

P. salmonis has many hypothetical proteins in islands, maybe because of the scarcity of gene characterization or curation. This is necessary to further elucidate the mechanisms in P. salmonis or understand the importance of specific domains for antibacterial agents’ development. Based on this and the percentage of factors within bacterial chromosomes (Table 5), it may be suggested that would be use metabolic mechanisms rather than antibiotic resistance.

The analysis of genes presents in selected islands and their follow-up revealed that hypothetical proteins stand out in the first place with a total of 17 genes, followed by mobile elements of IS group with almost 350 among all types, including unclassified transposases. It is speculated that the IS91 family originated by plasmid evolution

, and that stress generated at subinhibitory concentrations of antibiotics can result in rearrangements in the bacterial genome . Likewise, IS6 family has demonstrated it plays a key role in the incorporation of antibiotic resistance genes into other bacteria . However, among the islands selected, EM genogroup revealed more highly conserved mobile genetic elements in its own genogroup, leading us to propose that this genogroup could adapt better through this mechanism.Nonetheless, crucial genes related to pathogenic process has been found, such as the fur, recN and hslO gene. Fur is associated with iron uptake

, recN is associated with DNA repair in N. gonorrhoeae , and hslO protects cellular proteins from oxidative stress . If these are in islands and exhibit high conservation levels in the genome, it may be possible to investigate differential expression according to location in the genomic islands.The mazE gene was found in island 1 of Psal-009. It has been demonstrated that mazEF complex overexpression leads to biofilm formation under stressful conditions

. It was also found in plasmid 1 of the LF-89 strain, demonstrating the genomic plasticity of P. salmonis. All plasmids from specific strains present mosaic characteristics for being plasmids composed of genetic elements from different sources , and associated with antibiotic resistance genes . Moreover, some genes were present more than once in some genomes, simulating gene duplication behavior .

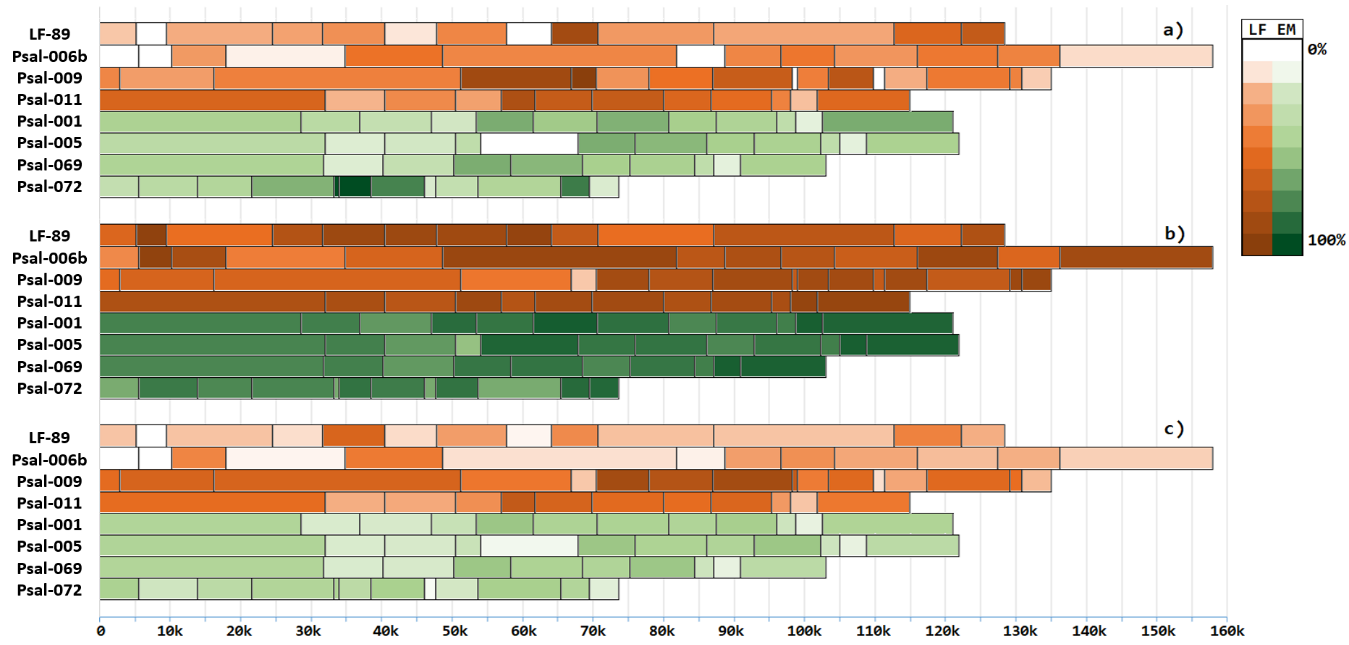

Figure 2 - Conservation of pathogenicity islands in genomes of P. salmonis strains, measured by BLASTp, distributed by strains, and ordered by chromosome location

Note: a – conservation of pathogenicity islands in plasmids of the same strain; b – conservation of pathogenicity islands in bacterial chromosomes; c – conservation of pathogenicity islands in bacterial plasmids

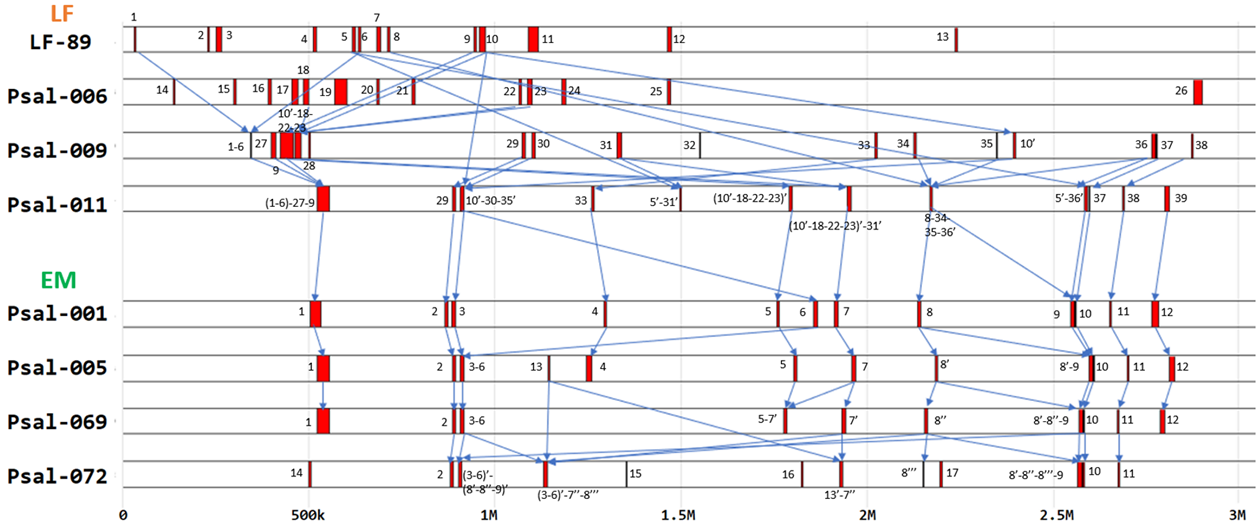

Figure 3 - Integrative synteny of pathogenicity islands in genomes with respect to original strains LF-89 and Psal-001, comprising a range between 0 and 3M base pairs

Note: older strains with pathogenicity islands for each genogroup; sequential numbers were used; for adjacent strains, the previous number was preserved if only one island with former content was present; the apostrophe (') was added if the previous island occurred in more than one island in a more recent strain; new islands unrelated to previous strains were identified with a new number

Due to the aforementioned, the need for identifying virulence factors among high- and low-virulence strains is reaffirmed through the use of genomic and proteomic tools

in order to determine the relevance of these pathogenic islands and identify adequate treatments, such as using an in silico approach to design a vaccine candidate.5. Conclusion

The EM genogroup presents similar islands between strains, in a greater proportion than the LF genogroup, with a lower variability. Among the islands observed, a low number of virulent factors was detected, these factors could accumulate in adjacent regions, leaving the islands as gateways for the pathogenic process. On the metabolic, resistance and symbiosis factors, despite presenting low identities, the genes themselves have the same names, reaffirming the type of non-virulent factor in genomic islands. Further studies consider the intervention of these islands and the impact on pathogenicity, in addition to validating the resistance, metabolic and symbiosis islands, regarding their role pertinent to the name of the subtype.